One of the most common things to configure in an application is some kind of credentials based connection. Typically this will be to a database or an API endpoint, but it doesn’t really matter too much - the examples in this post will be database configuration, but the principles are the same.

I’ll use the same example from the previous blog post and also put the configuration into the same github repo.

For simplicity’s sake, we’ll assume we’re trying to write a file called config.properties that has database configuration in the form of a simple jdbc type URL - e.g.

customerdb=jdbc:postgresql://db1.prod.example.com:3306/customers?user=webapp&password=changeme

storedb=jdbc:postgresql://db2.prod.example.com:3306/store?user=webapp&password=changeme2In terms of things that remain the same between environments, the DB type, DB name and username are likely to be consistent, and password, DB servers, and possibly port will vary. It’s very likely that DB type will be so consistent that we might hardcode it in the template rather than having unnecessary templating (there can be a temptation to template everything but the principle of YAGNI applies)

Between DBs in the same environment, there is little in common, but if more than one application uses the same DB then they might share configuration (possibly with different usernames and passwords, depending on security and monitoring requirements).

In terms of the location of credentials, we’ll store everything in the flat inventory files, with the exception of DB passwords which will be stored in separate variable files (in a separate repo, or even using ansible vault)

There are a number of ways to achieve this in Ansible.

Flat configuration strings

inventory/group_vars/all.yml

customerdb_dbname: customers

storedb_dbname: storeinventory/group_vars/production.yml

customerdb_host=db1.prod.example.com

customerdb_port=3306

storedb_host=db2.prod.example.com

storedb_port=3306inventory/group_vars/web.yml

customerdb_user=webapp

storedb_user=webappweb/templates/config.properties.tmpl.v1

customerdb=jdbc:postgresql://{{customerdb_host}}:{{customerdb_port}}/{{customerdb_dbname}}?user={{customerdb_user}}&password={{customerdb_password}}

storedb=jdbc:postgresql://{{storedb_host}}:{{customerdb_port}}/{{storedb_dbname}}?user={{storedb_user}}&password={{storedb_password}}Hierarchical configuration

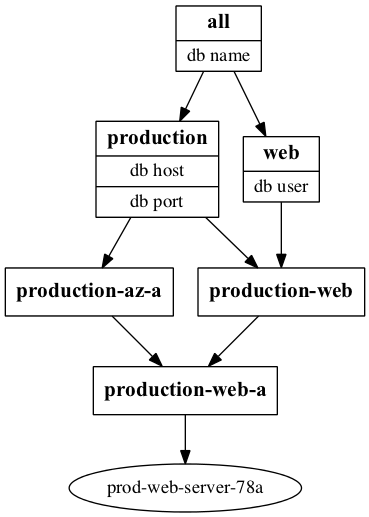

We can use hierarchical dictionaries of properties to configure properties in a slightly nicer fashion - rather than have variables named customerdb_dbname we can have a customerdb object that has a dbname property. And the storedb will have similar properties.

inventory/group_vars/all.yml

databases:

customerdb:

dbname: customers

storedb:

dbname: storeinventory/group_vars/production.yml

databases:

customerdb:

host: db1.prod.example.com

port: 3306

storedb:

host: db2.prod.example.com

port: 3306inventory/group_vars/web.yml

databases:

customerdb:

user: webapp

storedb:

user: webappThis version of the template is more sophisticated (and more complicated) but allows both DB connection strings to be expressed in a for loop. The modelling of the credentials (see below under Secrets) allows us to map per-database usernames and passwords.

web/templates/config.properties.tmpl.v2

{% for dbkey, db in databases.iteritems() %}

{{ dbkey }}=jdbc:postgresql://{{db.host}}:{{db.port}}/{{db.dbname}}?user={{db.user}}&password={{db.credentials[db.user]}}

{% endfor %}Before we use this template, we’ll discuss how we handle secrets.

Secrets

There are a number of approaches to storing secrets. We’ll show the old way by way of illustration so that we can run the playbook and generate the properties files.

I’ve actually committed dbsecrets.yml to the ansible-ec2-example repo for illustration, but it to keep sensitive information out of the playbooks repository it would perhaps be in a separate, more locked-down repo.

../../secrets/dbsecrets.yml

# v1

customerdb_password: changeme

storedb_password: changeme2

# v2

databases:

storedb:

credentials:

webapp: changeme2

customerdb:

credentials:

webapp: changemeweb/playbooks/dbconfig.yml

- hosts: web

connection: local

vars_files:

- '../../privaterepo/secrets/dbsecrets.yml'

tasks:

- name: create v1 config.properties

action: template src=../templates/config.properties.tmpl.v1 dest=/tmp/config.properties.v1

- name: create v2 config.properties

action: template src=../templates/config.properties.tmpl.v2 dest=/tmp/config.properties.v2Running this then generates two almost identical configuration files (the order of the two DB configurations is not guaranteed - which shouldn’t matter in general).

[will@cheetah playbooks (db_config)]$ ansible-playbook -i ../../inventory/hosts --limit prod-web-server-1a dbconfig.yml -vv

PLAY [web] ********************************************************************

GATHERING FACTS ***************************************************************

<prod-web-server-1a> REMOTE_MODULE setup

ok: [prod-web-server-1a]

TASK: [create v1 config.properties] *******************************************

ok: [prod-web-server-1a] => {"changed": false, "gid": 20, "group": "staff", "mode": "0644", "owner": "will", "path": "/tmp/config.properties.v1", "size": 184, "state": "file", "uid": 501}

TASK: [print databases] *******************************************************

ok: [prod-web-server-1a] => {

"msg": "{'storedb': {'port': 3306, 'host': 'db2.prod.example.com', 'password': 'changeme2', 'user': 'webapp', 'dbname': 'store'}, 'customerdb': {'port': 3306, 'host': 'db1.prod.example.com', 'password': 'changeme', 'user': 'webapp', 'dbname': 'customers'}}"

}

TASK: [create v2 config.properties] *******************************************

changed: [prod-web-server-1a] => {"changed": true, "dest": "/tmp/config.properties.v2", "gid": 20, "group": "staff", "md5sum": "f8c42bacfad384ecbff0f0d25673c5be", "mode": "0644", "owner": "will", "size": 184, "src": "/Users/will/.ansible/tmp/ansible-tmp-1396267209.8-73678850893620/source", "state": "file", "uid": 501}

PLAY RECAP ********************************************************************

prod-web-server-1a : ok=4 changed=1 unreachable=0 failed=0 Ansible Vault

Ansible vault allows you to encrypt your secrets with a password. These encrypted files can then be safely part of the repo.

The Ansible vault documentation is excellent and so as per usual, this is purely for expository purposes.

I’ll copy dbsecrets.yml to dbsupersecrets.yml and then encrypt it with

ansible-vault encrypt dbsupersecrets.yml

Should I then wish to edit the credentials,

ansible-vault edit dbsupersecrets.yml

will work. I used the excellent password ‘badpassword’ should you

wish to follow along.

Finally we can check this with a playbook that uses dbsupersecrets.yml and

run ansible-playbook with --ask-vault-pass

[will@cheetah playbooks (db_config)]$ ansible-playbook -i ../../inventory/hosts --limit prod-web-server-1a dbvault.yml -vv --ask-vault-pass

Vault password:

PLAY [web] ********************************************************************

GATHERING FACTS ***************************************************************

<prod-web-server-1a> REMOTE_MODULE setup

ok: [prod-web-server-1a]

TASK: [create v1 config.properties] *******************************************

changed: [prod-web-server-1a] => {"changed": true, "dest": "/tmp/config.properties.v1", "gid": 20, "group": "staff", "md5sum": "bfef3ceaeb19b490e82eb6b7b00b1456", "mode": "0644", "owner": "will", "size": 185, "src": "/Users/will/.ansible/tmp/ansible-tmp-1396437646.44-149420704780307/source", "state": "file", "uid": 501}

TASK: [create v2 config.properties] *******************************************

changed: [prod-web-server-1a] => {"changed": true, "dest": "/tmp/config.properties.v2", "gid": 20, "group": "staff", "md5sum": "65bdecffcdb33f6eb5ff3baf89ef8f1e", "mode": "0644", "owner": "will", "size": 185, "src": "/Users/will/.ansible/tmp/ansible-tmp-1396437646.66-279231900197780/source", "state": "file", "uid": 501}

PLAY RECAP ********************************************************************

prod-web-server-1a : ok=3 changed=2 unreachable=0 failed=0 And voilà, config properties files with the much more secure password of ‘Ch4ng3M3!’.

Addendum

03 April 2014

I realised my credentials modelling takes no account of environment. One simple way to do this is to store the environment name in the environment config file (i.e. add “env: production” to production.yml) and then have a hierarchy of vars files e.g. ../../secrets/production/dbsupersecret.yml

The nice thing about how Ansible Vault works is that you can choose to just encrypt the files under the production directory and have cleartext versions for dev and UAT, and the same templates and playbooks will still work (you only need to then pass –ask-vault-pass when running against production)

I’ve updated the github repo to reflect this, but the main change is to the location of the credentials files and the playbook:

- hosts: web

connection: local

vars_files:

- '../../secrets/{{env}}/dbsupersecrets.yml'

...